Corrections Officers: Addiction, Stressors & Problems Faced

The United States has the unenviable reputation for being the “incarceration nation,” the country that holds 25 percent of the prisoners in the world but only 5 percent of the general population of the world. While the causes of what led to this situation are hotly debated, the corrections officers who watch over these prisoners face traumatizing, life-or-death challenges that often go unnoticed and ignored, which can result in substance abuse and suicide.

If you’re a corrections officer in need of help, CALL our 24/7 Confidential Toll-free Number

Our compassionate Treatment Counselors are always available to assist you.

What Do Corrections Officers Do?

Understanding the scope of the situation means understanding what corrections officers are required to do as part of their job. In local jails, state prisons, and federal penitentiaries, correctional officers represent authority while looking after prisoners. This entails breaking up fights, ensuring that inmates follow the rules, and working with cooperating inmates in rehabilitation and “good behavior” programs. There are close to 500,000 men and women serving as correctional officers across the country.

For a corrections officer (also known as COs), everything they do is dictated by safety: their own safety, the safety of their colleagues, and the safety of the inmates they watch. To this effect, officers are required to complete training programs that cover the proper use of firearms, hand-to-hand combat, and the use of non-lethal weapons, like tasers, pepper spray, and batons. COs have to be in peak physical condition in order to survive and continue to function in the event of an attack.

It’s not just muscle. Officers have to be very observant, looking for signs of something amiss among a population of criminals and people who are generally hostile toward law enforcement and authority. Nonetheless, COs have to be able to foster working relationships with inmates, for the safety of the guards and inmates, and help inmates who are in trouble; recognizing the red flags of an emotional or mental problem can be the key to defusing a situation before it gets violent.

As much as guards are responsible for keeping prisons safe, they are also tasked with keeping the prisoners themselves safe. Jails and prisons are harsh, unforgiving environments, which often contribute to feelings of depression and anger. Correctional officers are trained to notify mental health counselors, or even intervene themselves, if they feel that an inmate’s mental health is deteriorating.

Part of this line of work may entail separating prison populations, to ensure that high-risk inmates are protected from those who may seek to assault, persecute, or even kill such prisoners. This could entail preventing certain members of the prison population (for example, rival gang members) from using common areas at the same time.

Building Working Relationships

Today, correctional officers are expected to play a more hands-on role with the inmates in their charge. As much as the job entails keeping an eye on prisoners, COs are trained and empowered to offer on-the-spot (and limited) mental health treatment, to be involved in job skills development programs, religious rituals, and substance abuse interventions. Since inmates who participate in these programs have a greater chance of living productive and peaceful lives upon their release, more and more correctional departments across the country are investing time and training for their officers to know how to respond in appropriate situations.

The key is to build working relationships with the inmates who are the most eager to have a better future outside prison, so correctional officers will work extra hard to meet those prisoners halfway.

This may mean that COs liaise with job placement, housing, and substance abuse rehabilitation agencies in the community, sometimes in their professional capacity as employees of state and local criminal justice departments.

Corrections Officers and PTSD

The theory of the job is commendable, but the reality on the ground is starkly different. The Guardian writes of the unofficial motto that exists among COs across America: “Prison guards can never be weak.” Figures are not easy to come by, but for the half-million officers who work in prisons, there are over 2.5 million prisoners to watch. Guards are exhausted, traumatized, and often ignored or shunned if they express any weariness or misgivings about the work they are required to do.

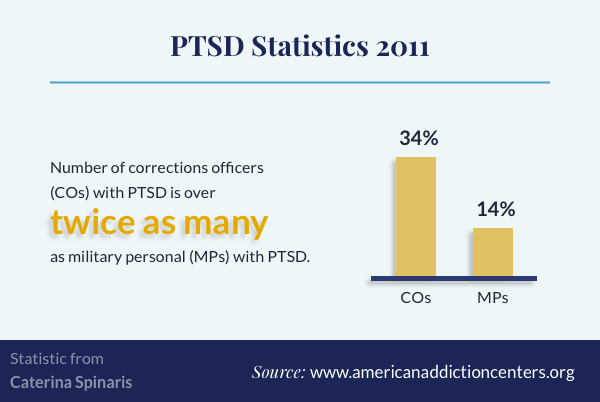

As a result, COs have rates of post-traumatic stress disorder that are more than double the rate that military veterans experience. This, in turn, affects prisoners; guards have been known to take their frustrations and anxieties out on inmates, incurring penalties that contribute to their mental health problems.

In 2011, Caterina Spinaris, an expert in clinical research on correctional policy issues, conducted an anonymous survey of COs, looking specifically for the signs of post-traumatic stress disorder: flashbacks, hypervigilance, suicidal thoughts, depression, and intrusive thoughts, among other symptoms. Spinaris found that 34 percent of corrections officers met the criteria for PTSD; by comparison, 14 percent of military veterans experience those symptoms.

When it came to suicide, COs take their own lives at a rate of twice that of both police officers and the general public. A national study published in the Archives of Suicide Research found that the risk of suicide among correctional officers was 39 percent higher than all other professions put together.

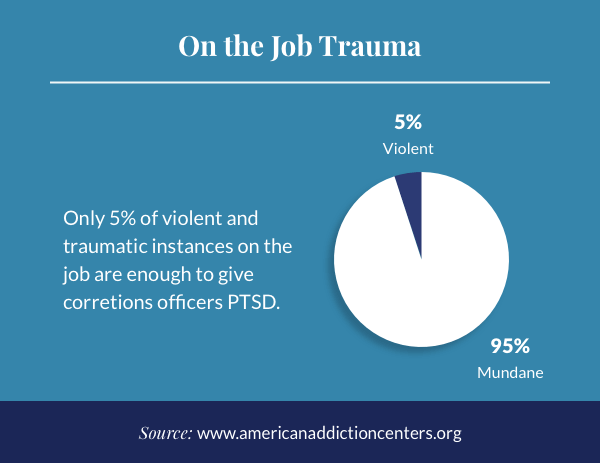

Michael Van Patten, one of the officers profiled by The Guardian, said that most of his job was “pretty mundane” – cell counts, watching what inmates are doing, even getting inmates extra toilet paper. This can go on for as long as 16 straight hours, sometimes without breaking for lunch. Such activities can account for 95 percent of the job.

What happens in the other 5 percent is what scars many officers: breaking up fights between inmates who are using smuggled weapons or their bare hands to try and kill each other; trying to stop suicide attempts and cleaning up an inmate’s cell after a successful attempt; and coming home with blood or human excrement smeared all over their uniform.

The worst part, said Van Patten, is that officers don’t know when the violence and intensity of that 5 percent will happen. This leads to guards being in a constant state of hypervigilance, a switch that they cannot simply turn off when they go home for the day. The high blood pressure from the “constant state of fight or flight,” in the words of the co-founder of the American Correctional Officer Intelligence Network, leads to heart attacks, ulcers, and reduced life expectancy.

Going into Battle Mode

On the face of it, the COs have control of the prison, but if the inmates wanted to, “they could take it.” Never knowing when that moment will come is akin to the environment that leads to PTSD in combat veterans; it is also similar to why women (and men) who have survived sexual assault develop PTSD, because they never know if they are really safe. For that reason, COs go into “battle mode” the second they enter a prison. Michael Morgan, a former officer at a state penitentiary in Oregon, described the experience to The Guardian like a soldier getting ready for war. For an eight-hour shift, anything can happen, and correctional officers have to be ready every second of those eight hours.

An environment like that is not conducive to dealing with the strain in a healthy manner. Officers are expected to process the trauma and swallow it as part of the job. There is an image to maintain, both for the benefit of the inmates, the general public, and other COs. Showing weakness could be the end of a career; it could also mean an opening for a hostile inmate to attack. As a result, COs often become more aggressive and withdrawn after spending enough time on the job. The warden at a correctional facility in Long Island says that officers become “robotic, emotionless,” both because of what the job did to them and also to protect themselves when they came to work.

Find Drug & Alcohol Treatment Centers Near You

-

- All Treatment Centers

- California

- Florida

- Nevada

- Rhode Island

- Texas

- Massachusetts

- Mississippi

- New Jersey

Nightmares and Suicide Attempts

Michael Van Patten related how watching an inmate die in agony (“coughing up lungs and screaming”) gave him nightmares, and no job training prepared him for the inability to mentally move on. Trevor, Van Patten’s son, also a corrections officer, was traumatized by seeing the remains of an inmate who was beaten to death by other prisoners. An hour after the murder, he went to lunch, then resumed his shift.

Trevor came home one day minutes before his father attempted to kill himself, but neither man was able to talk to the other about their shared experience. Michael had showed all the signs (insomnia, panic attacks, an obsession with working out, and heavy drinking), but COs don’t talk about PTSD. Many are afraid that a positive test for PTSD will get them decertified, unable to work in criminal justice or law enforcement. Because of this, they don’t talk to anyone about their problems; they drink harder and heavier; and they show up to work on time.

The head of the American Correctional Officer Intelligence Network says that COs are as much prisoners as the men and women under their charge. The only difference is that guards get paid for their time. When they hit rock bottom, their state and department health services are rarely sympathetic. It took nothing short of a panic attack for Michael Morgan to be diagnosed with PTSD to qualify for employment protection under the Americans With Disabilities Act. His state and department transferred him to a non-security job.

Morgan counts himself lucky but warns that “you can’t change a culture overnight.” Most COs are denied a healthy outlet for the stress they experience on the job; the president of the New York City Corrections Officers’ Benevolent Association told Newsweek that most officers find comfort in alcohol and drug consumption.

Divorce

The combination of mental health struggles and substance abuse takes its toll on the family; a Radford University study found that officers serving in correctional facilities have higher rates of divorce than the general population (which, in its own way, contributes to negative wellbeing and stress). The Journal of Family Violence writes of high rates of domestic violence carried out by COs, and The Atlantic says that violence directed toward wives or girlfriends by COs often goes unreported.

Female Officers

The common image of a correctional officer is a hulking man with a badge, but women also serve as COs, and they are not spared the abuse that comes with the job. A female CO told NBC Miami that she was sexually and physically assaulted by 17 inmates; however, despite reporting the incidents to her superiors, the managers of the Miami-Dade facility did not inform the police. Seventy-three days after the assault, the CO went over her supervisors’ heads and called the police herself. A corporal representing an association of correctional officers attributed the silence to an attempted cover-up. Women are more vulnerable than men for developing post-traumatic stress disorder, including substance abuse, in the aftermath of a traumatic event.

An Inherent Sense of Shame

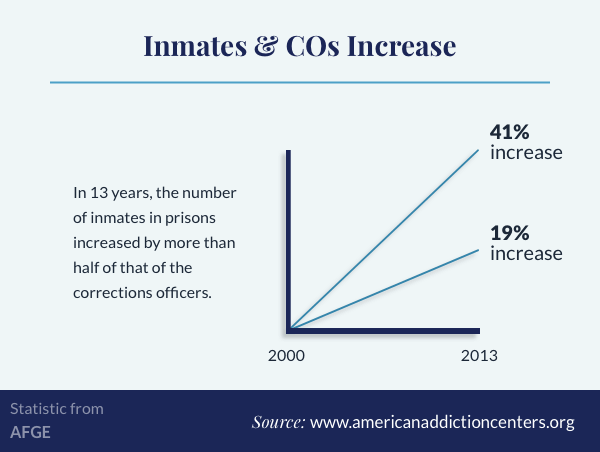

The environment of a corrections facility, already tense to begin with, is not conducive to sound mental health. The co-founder of the American Correctional Officer Intelligence Network explains that “incarceration nation” has overcrowded prisons across the country, and corrections departments are continually understaffed. The American Federation of Government Employees writes that the number of prison inmates in the 119 facilities operated by the Federal Bureau of Prisons went up 41 percent between the years 2000 and 2013, but the number of guards increased by just 19 percent.

This adds to the host of problems that correctional officers face; they are constantly abused, given no healthy outlet to let go of their tension, outnumbered, and even feel an “inherent sense of shame about what they do.” Officers rarely, if ever, talk to their families about what they do. Conflicts between work and family life are common, according to a study by the Correctional Management Institute of Texas at Sam Houston State University, which also wrote that COs do not get healthy amounts of sleep.

Some guards find themselves part of their respective prison’s black market. Whether intimidated by inmates, swayed by sympathy, or because they’ve simply “gone bad” (due to the stress), correctional officers are becoming an unlikely method for drugs and illegal materials to get into prison. It can happen because a guard has low self-esteem and craves adoration from inmates. Negative wellbeing is boosted by the risk of smuggling drugs, by flouting the rules, and by being in a position of power.

KFOR.com explains that the average pay for a CO is only $43,550, with certain states paying as low as $22,000. The desire to help an inmate is usually motivated by human kindness, not greed; but money is invariably involved, and what starts out with a pack of cigarettes can become cocaine and smartphone smuggling. One former corrections officer made $150,000 in a year by delivering contraband to the inmates under his watch. Additionally, once a CO starts helping an inmate, the balance of power shifts, and the inmate now has blackmail material with which to coerce the guard to continue the smuggling. In an environment where guards are already stressed, the pressure of being involved in criminal activity and being surrounded by hostile, dangerous people can be severe.

The Undeclared War Zone

Life as a correctional officer eats you up, said an Iraq War veteran to the Denver Post, which quoted Caterina Spinaris, an expert in clinical research on correctional policy issues, as saying that prison guards work in a warzone; they are subject to inhuman amounts of anxiety and personal abuse but have to be professional and stoic, to the point of turning off their humanity. As combat veterans can attest, simply turning it back on isn’t possible. A former manager of a corrections facility told the Post of how even at family outings, COs will always sit facing the exit and will always keep an eye on complete strangers, never letting their guard down and never relaxing.

For some families, the burden is too much, culminating in domestic violence (which entails physical or sexual abuse) and divorce. For some officers, consumed by guilt and stress, their lives end in suicide. No one, says the former manager, wants to hear or talk about the inmate who changed the television channel in a rival gang’s area of the prison and wound up dead the next day, a pencil driven through his ear and into his brain. Officers are left with no choice but to keep their distressing memories and nightmares to themselves, and then turn up to work the following day.

A doctor in Cañon City said that even though prison jobs offer a nice retirement, “many of these guys don’t live long after they retire.”

Changing the Corrections Culture

Gary Kapolites, a veteran CO talked to the Post about how the constant violence of the job (from the inmates to the guards, and vice versa) broke his will to continue working. Praising Caterina Spinaris’s work, Kapolites agreed with the idea that guards themselves are doing time, trapped by what they see every day, the uncertainty and fear of what might happen, and the inability to let go of their trauma when they return to their families. “A lot of them are unable to detach,” Kapolites said, and the only way they can channel their emotions is through alcoholism, domestic violence, and ultimately suicide.

But Spinaris’s focus is on changing things for the better, albeit slowly. She recounted success stories of guards being able to come to terms with the nature of their work, and some prison facilities are sending their stressed and burned out employees to her. She writes articles for a criminal justice resource website, breaking down concepts of psychological trauma, “corrections fatigue,” and post-traumatic stress disorder. For many COs, this may be the first (and only) time that their thoughts and feelings are addressed, and it suggests that the once-impenetrable culture of corrections officers is opening up to the dangers of the abuse and pressure that COs face every day.