Is Addiction a Disease or a Choice?

What Is Drug Addiction?

Drug addiction, in the simplest terms is the strong compulsion to get and use substances, even though a number of undesirable and dangerous consequences are likely to occur. Addiction has been described as a “medical disorder that affects the brain and changes behavior.”1 Various substances including alcohol, illicit drugs, prescription medications, and even some over-the-counter medicines may fuel the development of an addiction.

Certain behaviors such as compulsive gambling or sex are sometimes labeled as addictions, but here, the term “addiction” is reserved for drugs and alcohol.2

Models of Addiction

The Disease Model of Addiction

The definition of addiction varies among individuals, organizations, and medical professionals, and society’s viewpoints about addiction are ever-evolving. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) all similarly describe addiction as a long-term and relapsing condition characterized by the individual compulsively seeking and using drugs despite adverse consequences.1

These organizations call addiction a disorder or a disease because:1

- Addiction changes how the brain responds in situations involving rewards, stress, and self-control.

- These changes are long-term and can persist well after the person has stopped using drugs.

Comparing substance addiction to heart disease may help illustrate why it is defined as a disease by so many:1

- Both addiction and heart disease disturb the regular functioning of an organ in the body – the heart for heart disease and the brain for addiction.

- They both can lead to a decreased quality of life and increased risk of premature death.

- Addiction and many types of heart disease are largely preventable by engaging in a healthy lifestyle and avoiding poor choices.

- They are both treatable to prevent further damage.

Furthermore, since addiction is marked by periods of recovery and symptom recurrence (relapse), it resembles other diseases like hypertension and type-2 diabetes.3 These diseases are lifelong conditions that require continual effort to manage. Symptoms will likely return during periods where treatment compliance is low or absent, and symptoms will likely diminish when compliance to treatment begins again in earnest. 3

Is Addiction a Choice?: Opponents of the Disease Model

The idea that substance addiction is a disease is not, however, universal. Some would argue that addiction is not a disease because:4

- Addiction is not transmissible or contagious.

- Addiction is not autoimmune, hereditary, or degenerative.

- Addiction is self-acquired, implying the person gives the condition to himself.

Proponents of this way of thinking put much more emphasis on the social and environmental factors of addiction—one proponent claims that addictions may be “cured” by locking addicts in a cell where there is no access to substances—instead of on the brain changes that occur as a result of substance use.4

Some schools of thought view treatment for addiction as little more than the individual making the decision to stop using.5

Specific aspects of these opinions are hard to refute. For example, it is true that most substance use begins with a decision (although in many cases substance use began with a prescription from a doctor for a real medical problem and evolved into use).

But while no one forced an addicted person to begin misusing a substance, it’s hard to imagine someone would willingly ruin their health, relationships, and other major areas of their lives. Surely, if overcoming addiction were as easy as simply choosing to stop, the problem of addiction would be much easier to address and relapse would not be as common.

It should be noted that the “addiction is a choice” view is largely relegated to individuals and small groups. There are few, if any, nationally recognized substance use-focused organizations whose views have not evolved to understanding addiction as a disorder or disease. In fact, the NIH views the idea that addiction is a moral failing as an outdated, ill-informed relic of the past.6

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) no longer uses “addiction” as a term or diagnosis. Instead, the APA adopted the phrase “substance use disorder” as a way to describe problems related to “compulsive and habitual” substance use.7 The change was made specifically to avoid confusion surrounding the term addiction and it’s “uncertain” definition, as well as the negative stigma attached to the word. 7

No matter how one defines addiction or what term is used, what is clear is that addiction is an enormous problem in the U.S. that affects millions. Another irrefutable fact is that many drugs—both illicit and prescription—are quite addictive.

Why Are Drugs Addictive?

People get addicted to drugs for many reasons, but one of the major factors behind why drugs are so addictive is the rewarding, euphoric high they bring about. Drugs have the potential to significantly impact the systems in the brain relating to pleasure and motivation and make it difficult for other natural pleasures to compare.1

Every person experiences natural rewards in their life like a delicious meal, a favorite song, the pleasant feeling following exercise, or the happiness after sex, but drugs offer something more. The high that comes from using drugs is bigger, brighter, louder, and more gratifying than any natural reward, and it can make natural rewards seem small, dim, and quiet by comparison.

When drugs enter the brain, they can:1

- Mimic naturally occurring brain chemicals.

- Trigger the release of brain chemicals in large amounts.

- Prevent brain chemicals from being recycled and reabsorbed into the brain.

One of the brain chemicals often discussed in the addictive power of substances is dopamine.1 Scientists believe, when a rewarding event occurs, the brain releases dopamine to signal the experience and encourage repetition.1 In terms of natural rewards, this is healthy and keeps life going; consider the pleasure derived from sex: it encourages repetition, thus perpetuating the reproduction of the species.

Dopamine tells the brain that the experience of using a drug is important and should be repeated. The brain is programmed to remember the people, places, and things associated with the use, so it will be easier for the person to repeat the situation.

With repetition, these bursts of dopamine tell the brain to value drugs more than natural rewards, and the brain adjusts so that the reward circuit becomes less sensitive to natural rewards. This can make a person feel depressed or emotionally “flat” at times they aren’t using drugs.1 If natural rewards are a plate of broccoli, drugs are a huge bowl of ice cream, and broccoli is even less appetizing after ice cream.

Over time, the desire for drugs becomes a learned reflex—a person can be triggered to use by the people, places, and things that are linked to their drug use, just as someone might get hungry driving by their favorite restaurant, only the desire is likely to be much more overwhelming. Cravings can feel uncontrollable even years after a person gets sober.1

At the same time the drug is producing these changes in the brain that are associated with the development of addiction, the individual may also come to tolerate higher doses and even depend on the drug to feel well. 3 Tolerance and dependence develop because of adjustments the brain makes to manage the alterations that come from the repeated presence of a drug. Tolerance and dependence are two signs of a substance use disorder but may also develop to some extent in the absence of addiction. 3 So what are they?

- Tolerance is a state where the body’s reaction to the presence of a given amount of drug becomes diminished over time. To compensate, the person will consume a higher dose or consume it more often (or both).1 A growing tolerance to a substance’s effect and the ensuing increase in substance use may hasten the development of an addiction and increase the risk of overdose.

- Physical dependence is the state of needing alcohol or other drugs just to feel normal. 3 Without these substances in the system, withdrawal will arise, and depending on the substance, symptoms could range from irritating to life-threatening.7

Addiction and physical dependence are often talked about as though they are interchangeable; however, they are separate phenomena that can exist without the other. 3 Someone using their opioid pain medications as prescribed can develop some physiological dependence but may not exhibit the compulsive behaviors of addiction. Conversely, some drugs may be used in a compulsive manner that indicates an addiction without physically relying on it to feel well.

Symptoms of Addiction

The DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders includes:

- Taking the substance for long periods of time or in larger amounts than intended.

- Being unable to cut down or stop substance use.

- Spending a lot of time obtaining, using, and recovering from the effects of the substance.

- Experiencing cravings, or intense desires or urges for the substance.

- Failing to fulfill obligations at home, work, or school due to substance use.

- Continuing substance use despite having interpersonal or social problems that are caused or worsened by substance use.

- Giving up social, recreational, or occupational activities due to substance use.

- Using the substance in risky or dangerous situations.

- Continuing substance use despite having a physical or mental problem that is probably due to substance use.

- Tolerance, or needing more of the substance to achieve previous effects.

- Withdrawal, meaning that unpleasant symptoms occur when you stop using your substance of choice.

A medical professional may give the diagnosis of a substance use disorder if a patient exhibits 2 or more of the above within a 12-month period. Criteria 10 and 11 do not apply to someone taking a prescription drug as directed.

Causes & Risk Factors of Addiction

There is no single cause of addiction; people begin using substances for many reasons and one person’s path to addiction may look drastically different from that of another.

Apart from the case of beginning drug use via a prescription from a doctor, there are 4 main reasons people may try substances, according to NIDA:1

- To feel good. Drugs may lure people with the appeal of:

- A euphoric high.

- Feelings of power.

- Increased confidence.

- Energy.

- Relaxation.

- To feel better. Someone with anxiety, high stress, or depression might turn to drugs to try and manage distressing symptoms.

- To do better. Some drugs have the reputation of improving athletic or academic performance, so people may see them as a way of getting ahead or even just keeping up.

- To fit in or experiment. People, adolescents especially, may use out of sheer curiosity or to try and impress their peers.

People who have an intensely good experience their first time using begin to learn that drugs can make them feel great, and the foundations of addiction are set. Not everyone responds the same way to drugs and alcohol, however.

For years, experts have debated if it was nature (biology/ genes) or nurture (upbringing/ environment) that determined whether someone will become addicted. Now, the prevailing view is that there is no one thing we can look at to predict someone’s risk of developing an SUD—rather, the interaction of the person’s unique biology and environment BOTH influence how the drug will impact a person’s susceptibility to becoming addicted.1

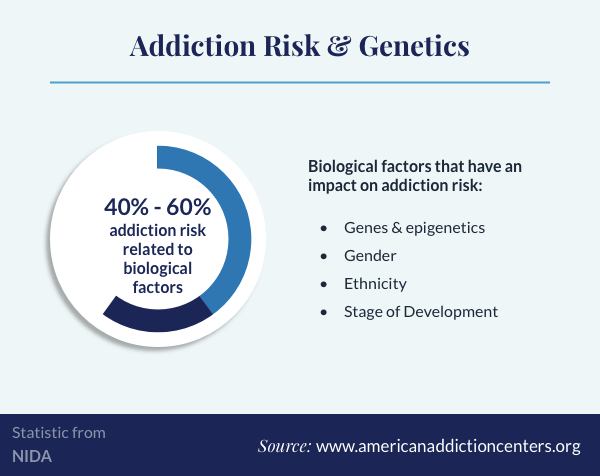

Biological Risk Factors for Addiction

Biological factors impacting addiction account for between 40% and 60% of someone’s risk for addiction.1Possible biological factors include:1

- Genes and epigenetics (the way environment impacts gene expression).

- Gender.

- Ethnicity.

- Stage of development.

The person’s developmental stage is particularly important, since teens who use drugs are much more likely to become addicted and remain addicted into adulthood.1

Environmental Risk Factors for Addiction

Environmental factors include all situations and experiences a person lives through. The most significant environmental influences include: 1

- Home environment.

- Family dynamics.

- Friends.

- School.

Each person will have a number of biological and environmental risk and protective factors.1 A risk factor is something that puts the individual in more danger of becoming addicted, while a protective factor is something that minimizes that danger.

Possible biological and environmental risk factors include:1

- Family history of addiction.

- Family history of mental illness.

- Chaotic home life.

- Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) like neglect or physical, mental, or sexual abuse.

- Negative attitudes of parents and friends.

- Unsupportive community.

- Poor school achievement.

- Easy access to drugs and alcohol.

Possible biological and environmental protective factors are:1

- No family history of addiction or mental illness.

- Good physical health.

- Supportive, involved family.

- Healthy relationships at home and in the community.

- Access to positive resources in the neighborhood like community groups, safe playgrounds, recreation centers, etc.

- Academic success.

- Strong impulse control.

Finally, the risk of addiction may be strongly impacted by the route of administration of the substance. Certain routes will produce stronger highs. For example, injecting opioids will produce a rapid intense euphoria that snorting or swallowing opioids can’t match.1

Intense highs that come on rapidly also tend to dissipate quickly,1 and the quicker comedown may further encourage drug use.

Addiction Treatment Process & Options

If you or your loved ones are drinking alcohol or using other drugs, it is never too early or too late to ask for help. Professional treatment for addiction is an effective way to address both your physical dependence and addiction. These programs don’t view the people who ask for help as “addicts” but as individuals struggling with a chronic condition affecting every aspect of their lives.

At the earliest stages of addiction treatment, a professional will conduct a thorough assessment to identify your current status, symptoms, and the most appropriate course of action to manage your recovery. An evaluation includes:8

- A complete physical health and mental health history.

- Information regarding the drug(s) being used, such as:

- The specific substance used.

- The duration, rate, and dose of use.

- If other drugs are used concurrently.

- Previous treatment attempts.

- Current stressors like:

- Financial problems.

- Legal issues.

- Risk for violence or suicide.

- Living situation.

Based on the information gathered during this assessment, you will be referred to a level of addiction treatment that best fits your condition.8

At the outset of addiction treatment, many people require a period of professional detoxification to allow the body to readjust to the lack of the drug (go through withdrawal) while under supervision.8 Professional detox is a necessary first step in treatment for many people getting sober, because quitting certain substances will bring about a range of distressing withdrawal symptoms that may venture into life-threatening territory.8

During medical detox, medications are used to manage withdrawal. Other detoxes, called “social” or clinically managed detox, emphasize the support and encouragement of staff in a safe environment to facilitate recovery but do not offer prescription medications for symptoms. These detoxes may not be safe for managing withdrawal from alcohol or sedatives and are usually not recommended in cases of opioid dependence due to the severe discomfort associated with withdrawal from these drugs.8

Detox, and the treatments that follow, can occur in inpatient or outpatient settings:8

- Inpatient treatment is any treatment requiring the individual to live at the facility while receiving services. Inpatient programs are often housed in hospitals or standalone treatment centers and vary in duration, with longer inpatient treatment often referred to as residential treatment. Inpatient treatments offer more intense services for people with greater symptoms and a lack of healthy support at home.

- Outpatient treatments permit the individual to attend services during the day and sleep in their own bed at night. Outpatient is usually a better fit for people with less severe addictions and/or strong social networks. Outpatient treatments may continue for years and levels of care include:

- Partial hospitalization programs (PHPs). This highest level of outpatient that includes many hours of services each day, 5 days per week.

- Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs). Slightly less intensive than PHPs, IOPs provide between 6 and 9 hours of treatment each week.

- Standard outpatient. This is the least time intensive outlet for outpatient care, offering hour-long sessions weekly or monthly.

For many, addiction treatment is a lifelong process with ongoing professional treatment and aftercare options to maintain recovery. Since longer periods of treatment are linked to longer periods of recovery, staying in treatment for an adequate amount of time (as recommended by your treatment staff), engaging in aftercare, and participating in recovery groups can be extremely beneficial.3

Whether you think addiction is a disease or not, everyone can agree that addiction is a serious problem that adversely affects the lives of the people using substances as well as the people in their lives. The suffering that comes along with addiction can be immense, but treatment offers a ray of hope for the future.

Admissions navigators at American Addiction Centers (AAC) can answer questions about our treatment facilities across the U.S. and help you or your loved one begin treatment today.